IN 1977, ONE SONG TURNED A $300 MILLION MOVIE INTO A TRUCKER ANTHEM

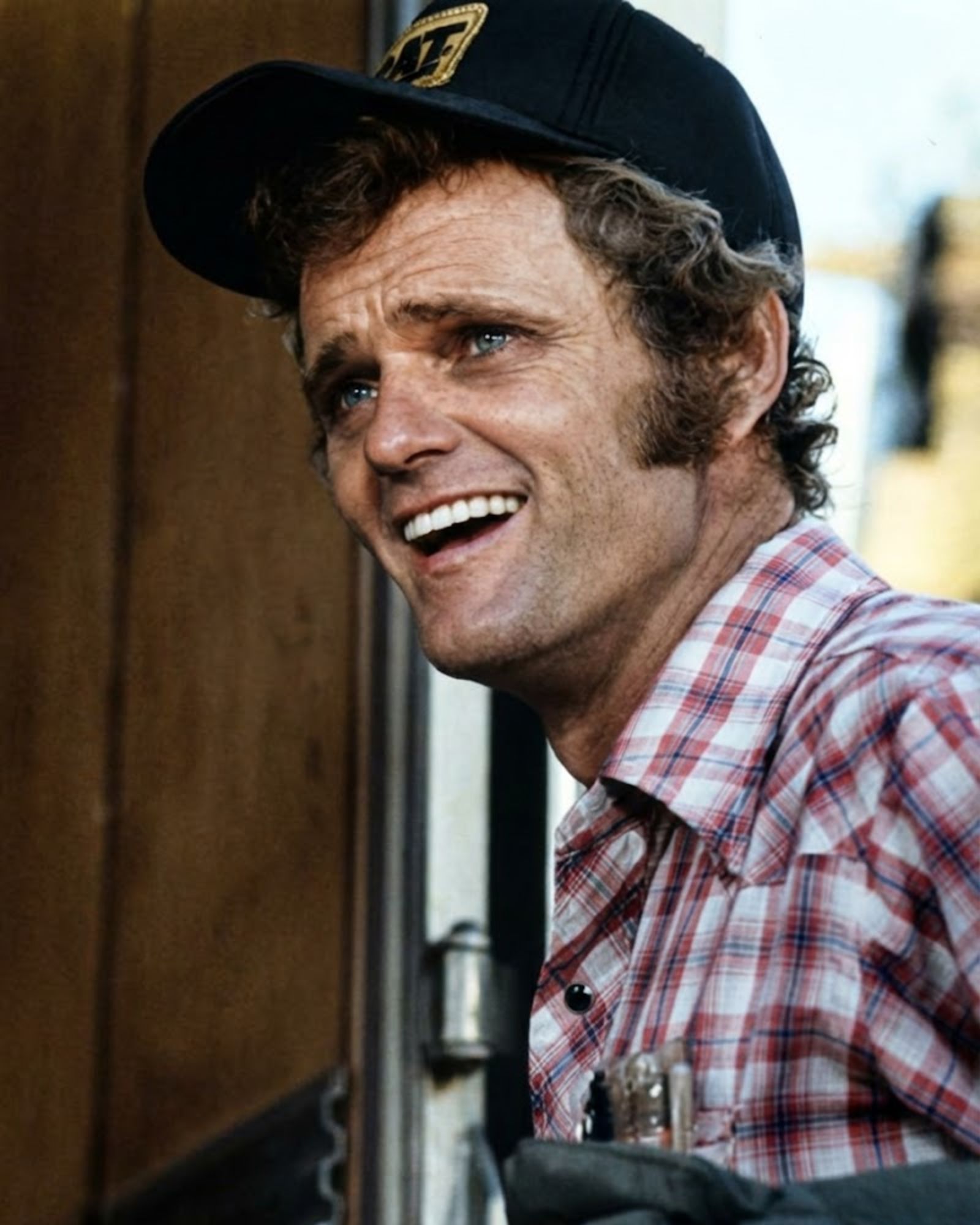

At first, nobody treated it like history in the making. It was just another movie song—written quickly, recorded between takes, meant to roll under opening credits and fade out when the story moved on. Even Jerry Reed didn’t talk about it like a career moment. He played it loose. Smiled through it. Let the groove do the work.

But the groove sounded different.

The opening beat of East Bound and Down didn’t feel like Nashville polish. It felt like motion. Like tires humming on hot pavement at two in the morning. Like coffee that’s gone cold but still gets the job done. Reed’s voice didn’t try to sell a message. It just told the truth in passing, the way truckers talk when the road is long and nobody’s listening.

The song was written for a film that would explode far beyond expectations. Smokey and the Bandit became a box-office giant, eventually pulling in what would amount to hundreds of millions worldwide. Audiences laughed, quoted lines, and fell in love with fast cars and fast talk. But something else happened quietly, far from movie theaters.

When the song hit the airwaves in 1977, truckers heard it immediately.

Not as entertainment. As recognition.

CB radios lit up across interstates and state lines. Drivers turned the volume knobs all the way right, windows down, engines steady. Some swore the rhythm matched the pace of an eighteen-wheeler better than any metronome. Others joked that if you played it too loud, the truck might start driving itself. It wasn’t about rebellion or outlaw fantasy. It was about movement. About staying awake. About feeling less alone between exits.

By the time the song climbed to No. 2 on the country charts, the ranking felt irrelevant. Charts belonged to offices and magazines. This song belonged to the road.

Stories started spreading—some true, some embellished, all told with confidence. One claimed a driver in Texas used the song as a timing cue to outrun a storm by minutes. Another insisted it helped a convoy stay together through fog so thick you couldn’t see the hood ornament. There was no proof. Nobody needed any. On the highway, belief travels faster than facts.

What truckers heard in East Bound and Down wasn’t hidden symbolism or clever songwriting. It was permission. Permission to keep going. Permission to laugh at trouble. Permission to treat the journey itself as the point, not the destination.

That’s why it lasted.

Long after the movie posters faded and newer songs chased newer trends, the track stayed alive in places no chart could measure. Late-night AM stations. Worn cassette tapes. Radios mounted above dashboards scratched by decades of miles. It became a kind of shorthand. Play this, and you’re part of something. You understand the rhythm of the road.

So was East Bound and Down just a movie song?

Technically, yes. It was written for a film. Recorded on a schedule. Released with a purpose.

But truckers heard something else. They heard honesty without effort. Momentum without ego. A song that didn’t tell them who to be, only reminded them of what they already were—people in motion, chasing daylight, trusting the next mile.

And sometimes, that’s all a song needs to become a signal.