THE NIGHT WAYLON JENNINGS WROTE “GOOD HEARTED WOMAN”

A Song Born Far From the Studio

They say outlaw songs aren’t born in studios — they’re born in bars.

One dusty night in 1969, Waylon Jennings wasn’t chasing radio hits or chart positions. He was sitting in a half-empty honky-tonk on the edge of Phoenix, where the neon sign outside buzzed louder than the jukebox inside. No stage lights. No record executives. Just warm beer, cigarette smoke, and people too tired to pretend they were anything but lonely.

Waylon kept his hat low and his guitar case closed. He didn’t come to play. He came to listen.

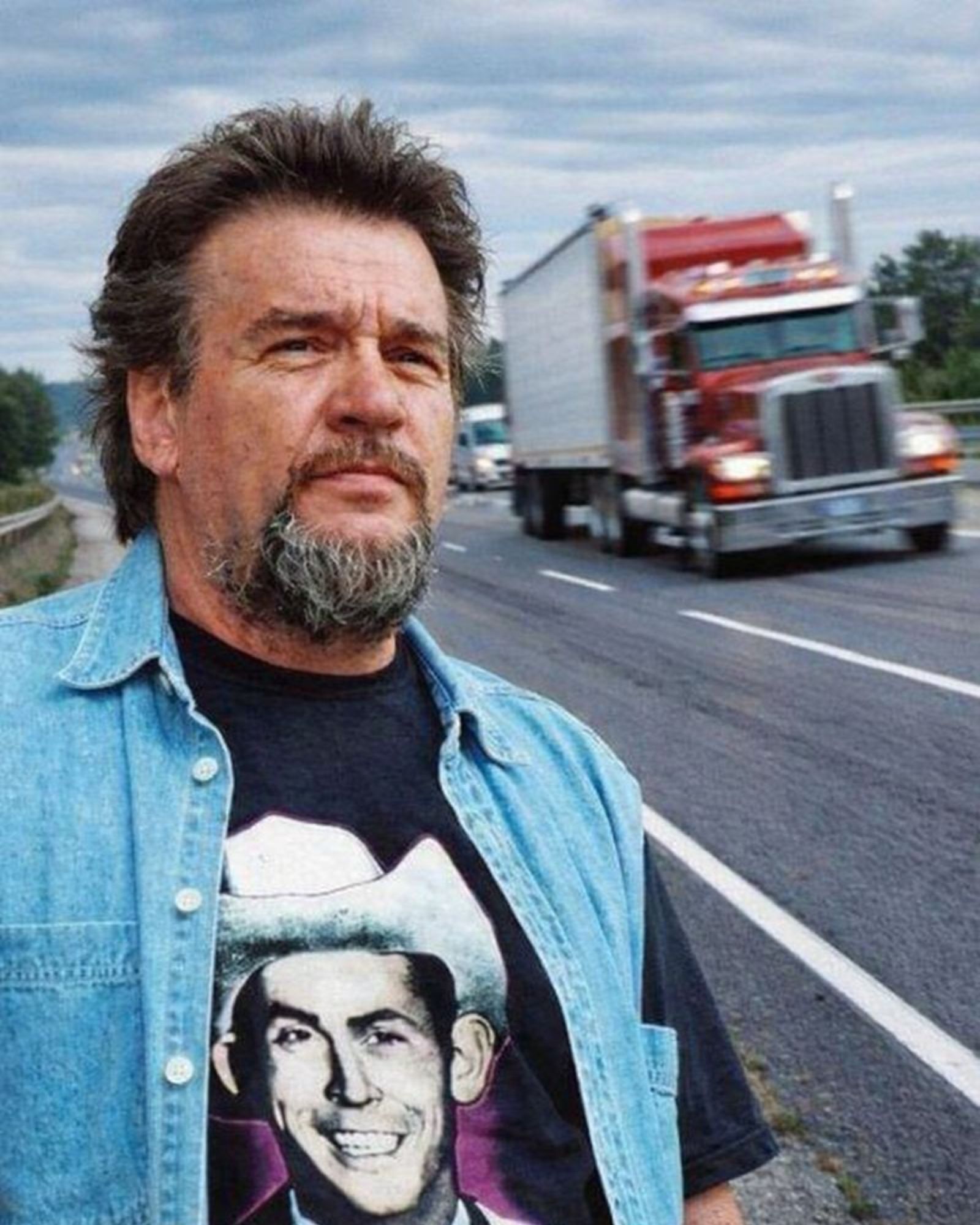

At the next table, a waitress in a wrinkled uniform counted out her tips in nickels and dimes. Across from her sat a truck driver with sunburned hands and a voice rough from long roads. He kept apologizing for being gone so much. She kept saying she understood, though her eyes said something else.

Waylon heard stories like that everywhere he went. But that night, the words landed differently.

One Sentence That Changed Everything

The waitress finally laughed, tired but honest, and said:

“Loving a man like you is like loving the highway. You never really come home.”

Waylon didn’t look up. He reached into his pocket, pulled out a matchbook, and wrote a single line across the cardboard:

“She loves him in spite of his ways…”

He didn’t know it yet, but that sentence would become the spine of “Good Hearted Woman.”

It wasn’t a love song about roses or promises. It was about survival. About women who learned to love absence as much as presence. About men who couldn’t stop wandering even when they wanted to. It wasn’t pretty. It was honest.

From Barroom Truth to Song

Back at his place, Waylon kept turning the line over in his mind. He added verses like someone stitching together pieces of a life he already knew too well. He sang about gamblers, singers, and men who wore out their welcome everywhere except at home. He sang about women who stayed anyway.

Some say Willie Nelson helped shape the song later, turning it into something both rough and tender. Others say Waylon already had the heart of it before sunrise. What matters is this: the song didn’t come from imagination alone. It came from listening.

When Waylon finally recorded “Good Hearted Woman,” it didn’t sound polished. It sounded lived-in.

A Song That Belonged to Everyone

By the time it reached the radio, the song no longer belonged to Waylon. It belonged to every waitress who closed a bar at 2 a.m. It belonged to every trucker’s wife who slept with the television on just to hear another human voice. It belonged to every woman who loved a man who loved the road more than sleep.

Fans heard themselves in it. Not the glamorous part of country music — the quiet part. The part that waits. The part that forgives. The part that understands without asking too many questions.

The Outlaw Sound With a Soft Heart

“Good Hearted Woman” became more than a hit. It became a definition. Outlaw country wasn’t just about rebellion. It was about refusing to lie. It told the truth about broken schedules, broken promises, and unbroken love.

Waylon would later sing it on bright stages under clean lights, but the soul of the song always stayed in that dark bar in Phoenix — with a tired waitress, a restless man, and a songwriter who knew when to stay quiet.

Why the Song Still Matters

Decades later, the world has changed. Trucks move faster. Songs are made on laptops instead of matchbooks. But “Good Hearted Woman” still feels familiar.

Because there are still women who wait.

There are still men who wander.

And there are still nights when a single sentence overheard in a bar can turn into a song that lasts forever.

Not every love story needs a happy ending.

Some just need a good heart to survive the road.