When Nashville Turned Its Back: The Firing of Hank Williams and the Louisiana Return That Defined Him

Introduction

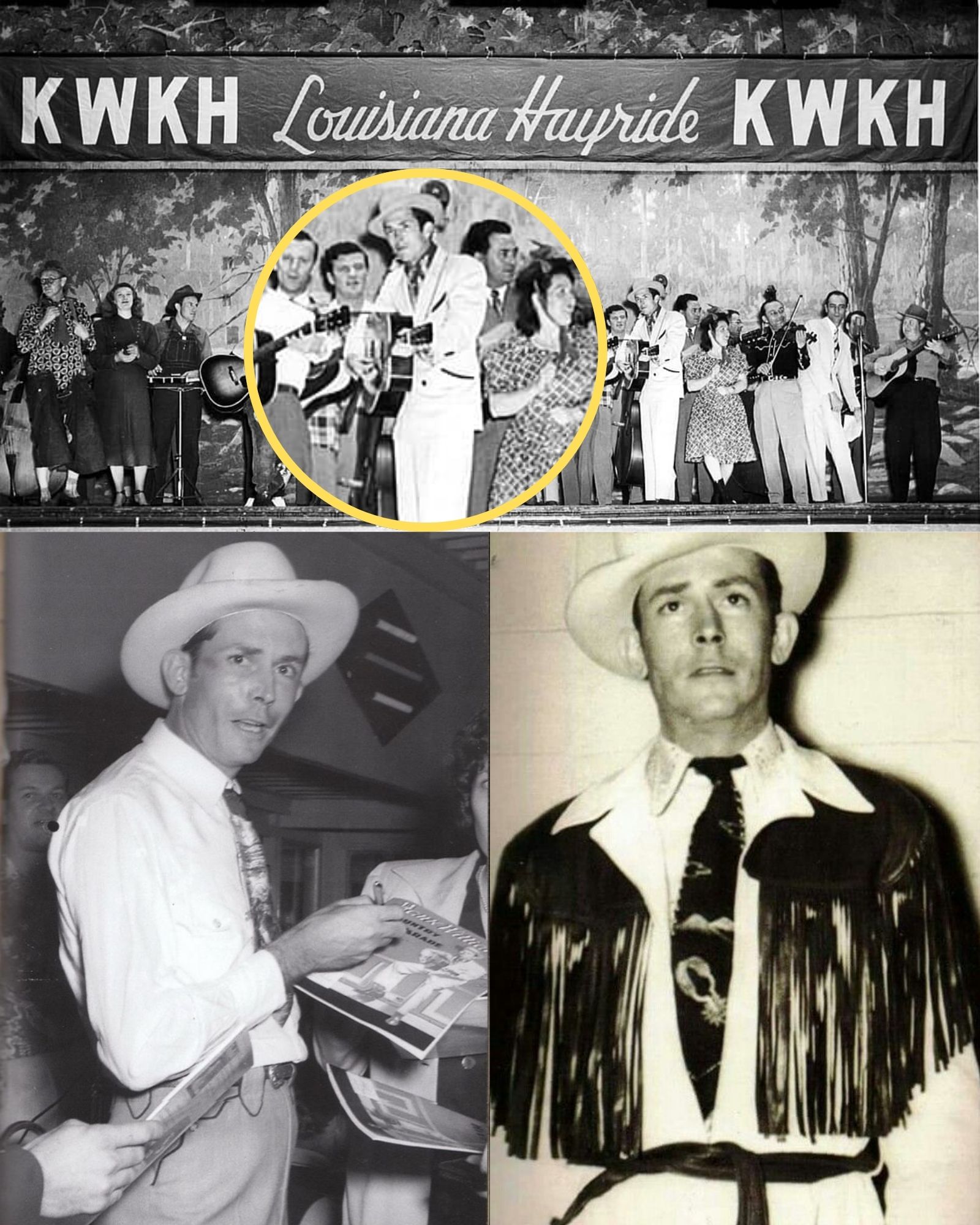

Every legend has a fracture. For Hank Williams, the fracture came publicly in 1952—when he was dismissed from the Grand Ole Opry. To many, it was unthinkable: how could the king of country ever be banished from its most hallowed stage? Yet it happened. And in the fallout, Hank found himself returning to Louisiana, to Hayride stages where his voice first rose. That return would become more than a comeback—it would reveal the fragile boundary between genius and self-destruction.

The Rise, the Dependence, and the Breaking Point

Hank Williams had long shot to fame via the Louisiana Hayride, which began broadcasting him in 1948. He later joined the Grand Ole Opry, becoming a central figure in country radio and performance. But by 1952, his personal life was catching up. Alcoholism, missed shows, erratic behavior, and chronic back pain plagued him. On August 9, 1952, Hank failed to appear at an Opry engagement. That no-show became the final straw. The Opry’s manager, Jim Denny, had pleaded for one more chance. When Williams again missed an Opry-sponsored event drunk the next day, action was taken: he was fired.

The Opry didn’t intend to cast him aside forever—they framed the dismissal as a warning, a chance for redemption. But for Hank, the damage had been done. His status within Nashville’s inner circle fractured.

The Return to Louisiana: Homecoming or Last Stand?

Rather than fade, Williams turned back to Shreveport, the city whose radio waves underwrote his earliest growth. When he stepped onto the Louisiana Hayride stage in September 1952, the reception was thunderous. He performed “Jambalaya (On the Bayou),” a song he’d recorded just months earlier, and the crowd roared as if he’d never left. Announcer Horace Logan greeted him as a returning son: “It’s been about two years since you’ve been home, boy.” That moment spoke of loyalty, of identity, of roots that refused to detach even in crisis.

Yet this homecoming carried weight. The firing had undermined his Nashville standing, while the return to Hayride showed that his legacy was rooted in places more than just power rooms. It revealed where the public loves him more than an institution can reject him.

The Aftermath and Legacy

Even after the dismissal, Hank continued to record and chart hits. “Jambalaya (On the Bayou)” became one of his most enduring songs. But the firing and the return also foreshadowed his tragic end: Hank would never reclaim full favor in Nashville. He died just months later, on New Year’s Day 1953, in the backseat of a Cadillac while en route to a concert. In the years since, fans have petitioned the Opry to reinstate him posthumously—an acknowledgment that his significance couldn’t be erased simply by exile.

His story remains a cautionary tale: that institutions can hold power over art, but art can also transcend institutions. The arc from firing to return to legacy is part of what makes Hank Williams not just a musician, but a myth.

The image of Hank Williams returning to Louisiana after a public dismissal carries deep resonance. It forces us to ask: what matters more—status or voice? When Nashville shut him out, Louisiana welcomed him back. That tension defines the dramatic heart of his story. Genius and exile walked hand in hand, shaping a legacy that still speaks louder than reputation.