“LORD, MAYBE THIS OUTLAW BIT’S DONE GOT OUT OF HAND.”

It wasn’t a lyric yet — just a broken whisper in the dark.

The air in the studio was thick that night, filled with cigarette smoke, the hum of amplifiers, and a man’s quiet realization that the story he’d been selling had finally come to collect its debt.

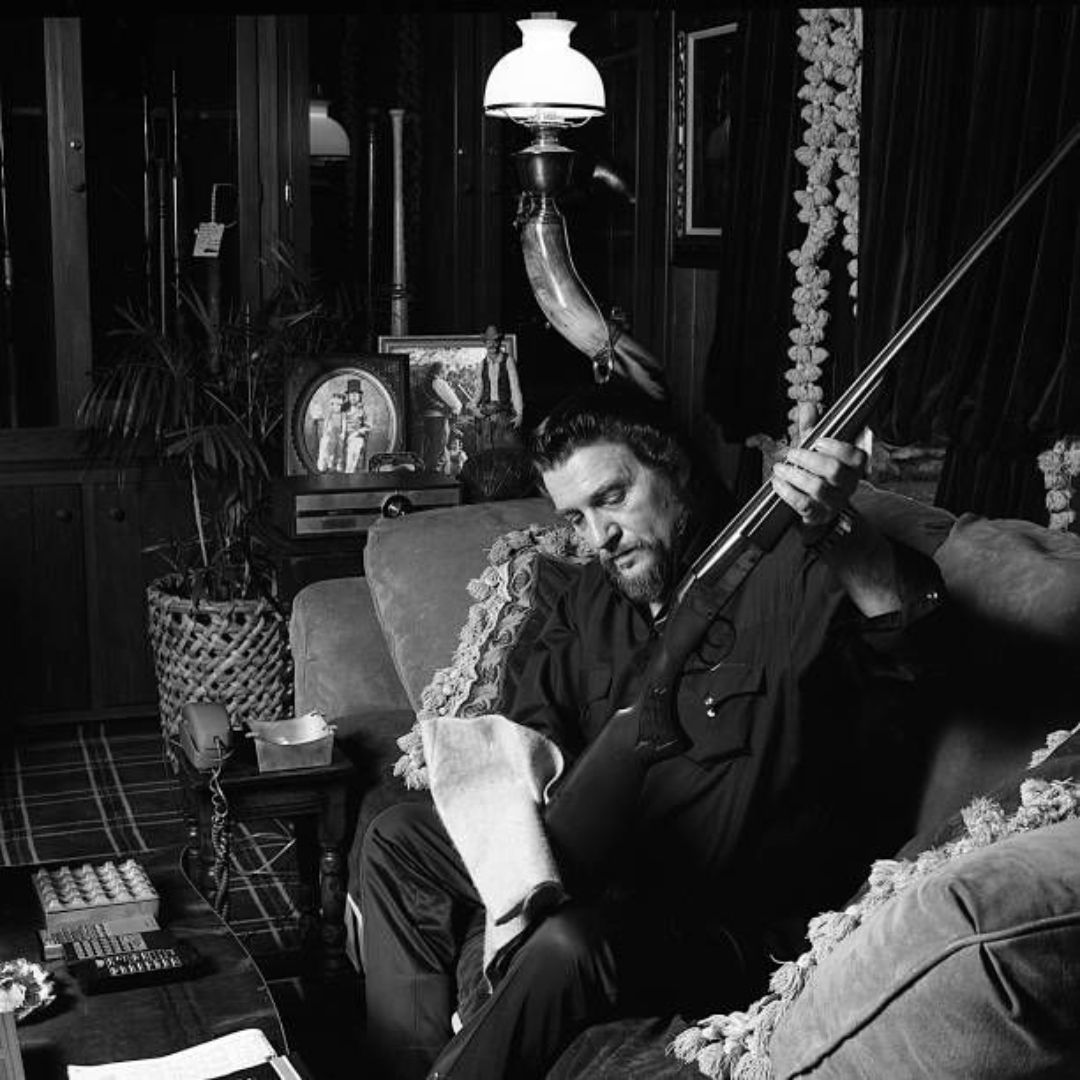

Waylon Jennings had spent years building the outlaw myth — the hat, the boots, the attitude that defied Nashville’s clean-cut image. Fans loved it. The industry feared it. And somewhere in between the fame and the fog, Waylon started believing in it himself. Until August 1977 — when flashing red lights from an FBI helicopter poured through the studio windows.

They weren’t coming for a concert. They were coming for him.

Inside, a package sat on the table — cocaine sent through the mail. Outside, agents with warrants and radios swarmed the room. Waylon, still holding his guitar, looked up and muttered the line that would haunt him forever:

“Lord, maybe this outlaw bit’s done got out of hand.”

That moment didn’t end his career. It saved it.

Because for the first time, the “Outlaw” wasn’t a stage act — it was a mirror. The song he later wrote from that chaos wasn’t just confession; it was catharsis. He turned guilt into melody, fear into rhythm, and irony into one of the most brutally honest tracks in country music history.

Released in 1978, “Don’t You Think This Outlaw Bit’s Done Got Out of Hand” stripped away the romance of rebellion. It was Waylon laughing at himself, warning others, and reclaiming his own soul in the same breath.

The lyrics cut deep: part satire, part sermon, part survival story. And only someone who’d seen both sides of the stage lights — the glory and the ruin — could’ve sung them that way.

In the end, it wasn’t about drugs, fame, or law enforcement. It was about a man who looked his legend in the eye and said, “Enough.”

Waylon Jennings didn’t just write a song that night. He wrote his reckoning — and somehow, it made the world love him even more.