LONG BEFORE IT HAD A NAME, THE CHET ATKINS STYLE WAS ALREADY RESHAPING WHAT A GUITAR COULD BECOME

A Quiet Revolution in a Loud Industry

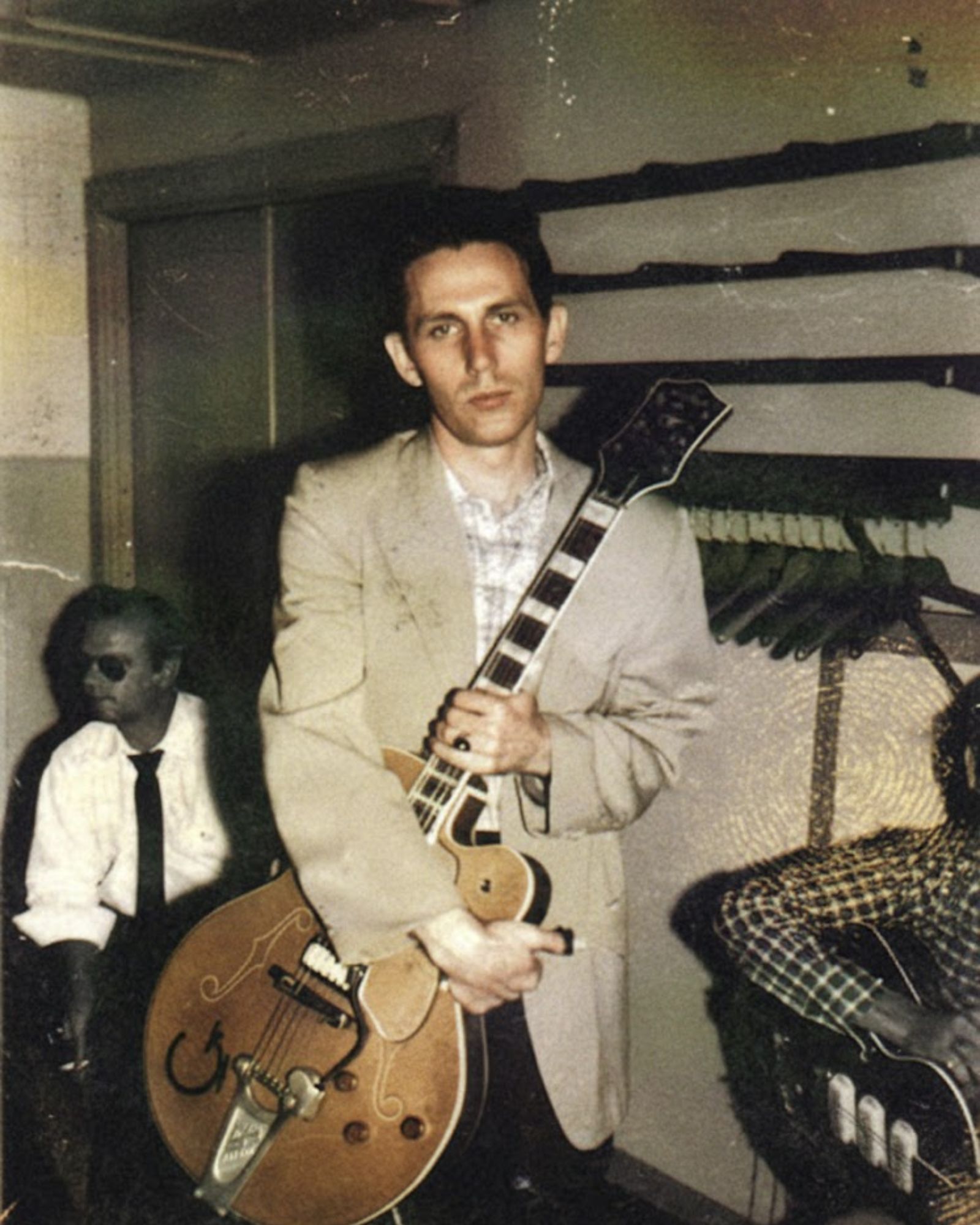

Between 1953 and 1956, while Nashville was still clinging to raw honky-tonk rhythms and jukebox heartbreak, Chet Atkins was doing something few noticed at first. He wasn’t shouting for attention. He wasn’t chasing trends. He was sitting in small studios, guitar in hand, teaching an instrument how to speak in full sentences.

Albums like Stringin’ Along, A Session with Chet Atkins, and Finger Style Guitar arrived without drama. No manifesto. No grand announcement. Yet inside those recordings, a new language was forming — one where a single guitar could sound like an entire conversation.

Two Hands, One Voice

Witnesses from those early sessions later described an eerie calm in the room. Atkins’ thumb kept a steady bass pulse, like footsteps down a hallway. Meanwhile, his fingers shaped melody and harmony above it, moving independently, as if guided by separate minds.

It felt less like playing and more like architecture — notes placed with intention, silences treated as carefully as sound. Some engineers claimed the walls themselves seemed to listen. Others joked that the guitar was learning manners.

What mattered most was this: the guitar was no longer just an accompanist. It became a narrator.

Blending Worlds That Rarely Met

Atkins didn’t choose between country, jazz, pop, or light classical music. He folded them together.

A country rhythm would carry a jazz-flavored chord.

A pop-style melody would float over classical balance.

A folk instrument suddenly behaved like a small orchestra.

This mixture made his sound feel refined without becoming distant. It was elegant but still human. Listeners didn’t always understand what they were hearing — only that it felt different. Cleaner. Smarter. Almost European in mood, yet unmistakably American in heart.

The Rumors That Followed the Sound

Stories began to circulate. Young guitar players, it was said, wore out their needles replaying those records. Jerry Reed reportedly tried to copy the bass lines first, then the melodies, and finally the mysterious space between them.

Decades later, names like Tommy Emmanuel, Mark Knopfler, and even George Harrison would trace their fascination with fingerstyle guitar back to these early Atkins recordings. Whether myth or memory, the legend stuck: this was where they learned that a guitar could sing alone.

The Birth of a Style Without a Name

No one called it the “Chet Atkins style” at first. That label came later, when the sound had already escaped the studio and reshaped expectations.

By the time Nashville polished its edges into what became known as the “Nashville Sound,” Atkins’ fingerprints were already there — smoother textures, clearer arrangements, and a guitar that carried emotional weight without shouting.

Country music became more accessible. More melodic. Less rough around the edges. And the guitar was no longer stuck in the background.

What Really Happened in Those Rooms?

Perhaps the greatest mystery is how intentional it all was.

Did Atkins know he was changing the future?

Or was he simply solving small musical problems day by day — how to make one instrument sound fuller, kinder, more complete?

Some say the magic was accidental. Others insist it was quiet genius. The truth likely lives somewhere in between: a man listening closely to what his hands were capable of, and trusting them.

Why This Era Still Matters

Those 1953–1956 recordings were not just albums. They were blueprints.

They taught future musicians:

-

That complexity could feel simple.

-

That technique could serve emotion.

-

That a guitar could tell a story without lyrics.

What began as modest studio sessions became a foundation stone for modern fingerstyle guitar and the refined sound of country music itself.

And so the story remains half-told — not because it lacks facts, but because its real power was invisible at the time.

A man.

A guitar.

And a sound that learned how to speak before anyone thought to give it a name.